Sharing my research and methods: Towards more inclusivity in pattern making

I have been wanting to write this article for a quite a while. But I haven’t had much free time lately, which is to say, ever. I know I am not alone in this feeling- who among us doesn’t complain about time passing too quickly?

Just a warning- throughout this article I am going to use the words BIG - FAT - PLUS SIZE - STANDARD SIZE - RACISM and FAT-PHOBIA. In doing so, I am in no way trying to cause controversy, but am hoping instead to share with my readers what I myself have learned these past months, as well as share the size chart and pattern grading guidelines that I have developed.

At the beginning of 2019, after decades of exclusion, inclusivity in the world of fashion slowly began to gain momentum. The topic of inclusivity was on everyone’s lips, due in large part to activists who knew how to use their platforms to make their voices heard. On social media, in the fashion world and especially in the sewing community, things slowly began to change.

![]()

Why do most ready-to-wear fashion brands stop at size 44/46 (UK 16/18 - US 12/14) ?

If we rely on the study of Sabrina Strings, author of Fearing the black body, the origin of this limited range of sizes could be based in part on the fat-phobia which would have taken root between the Renaissance and the 19th century. According to her research, during the Renaissance, at the very beginning of the slave trade, the feminine beauty ideal was that of a plump and proportioned body regardless of skin color (let’s recall that the Greco-Roman antiquity constitute the criteria of the aesthetic judgment of the time). Over time, this approach changed and an aversion to black and big bodies most likely arose between the Renaissance and the 19th century with the birth of “race science”. In the 18th century philosophical texts brought about a new vision, these "scientists" of the era were keen to mark a hierarchical difference between blacks and whites in terms of both physics and behavior. Europeans were portrayed as disciplined, rational and self-controlled while Africans were seen as sensualists, flesh-and-blooded. Simply stated, according to this schema of thought, the rounder or more athletic body with unbridled manners of the black slave was scorned and one had therefore to be white, slender and in control. When you think about it, a form of this stigma still exists today: thin people are seen as energetic, dynamic, and reliable while fat people are associated with laziness, lack of willpower etc. I won’t dive any further into this subject, but I found interesting to mention the research of Sabrina Strings who is the first to have made a real study on the roots of fat-phobia. Her book is fascinating and if you're interested, I urge you to check out the resources below.

Resources :

- Article (eng.)

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/fat-shaming-race-weight-body-image-cbsn-originals/

- Book (fr.)

Fearing the black body par Sabrina Strings

- Podcast (eng.)

https://anchor.fm/love-your-bod-pod/episodes/88-Why-Do-We-All-Want-To-Be-Thin--The-Racial-Origins-of-Fat-Phobia-with-Sabrina-Strings--PhD-ed1qu6

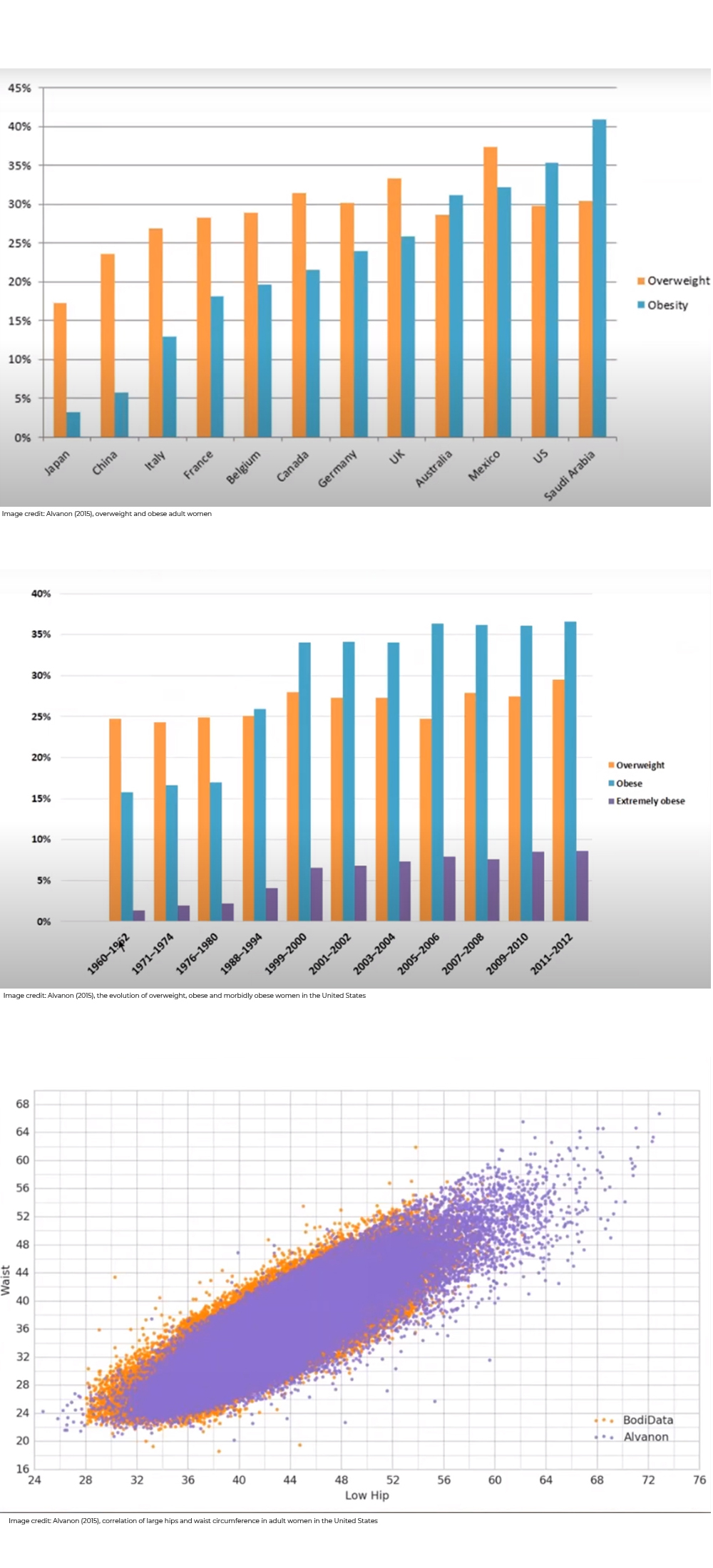

![]()

In ready-to-wear fashion, a pattern is developed based on a sample size that is generally a 36 (UK 8 - US 4) or eventually a 38 (UK 10 - US 6). From there it is graded into both smaller and bigger sizes. The technical designers that work for the top ready-to-wear brands on the market have been trained to work using this small body frame as the standard. In high fashion, the norm is a size 36 (UK 8 - US 4 ) with a B cup. In concrete terms, to the question, “At what size does plus size begin?” the typical answer would be from size 42 (UK 14 - US 10 ) in high fashion and from 44/46 (UK 16/18 - US 12/14) in ready-to-wear clothing. Indeed, the most recent dress form offered by the brand Stockman Paris, used by the biggest names of high fashion and the fashion industry, stops at size 46. It is, as a consequence, hard for a pattern-maker, to find a dress form beyond this size.

Pattern grading consists of using a mathematical formula in order to elongate and enlarge clothing. One single method or formula CANNOT be used endlessly. It is not possible to grade a pattern based on the measurements of a size 36 (UK 8 - US 4) all the way to a size 54 (UK 26 - US 22). After 3 or 4 sizes, grading is going to contort the pattern. Basically, the sample is usually developed for a size 36, i.e. already at the bottom end of the size range instead of using a more average size (a 40 for a size range that goes from 32 to 46, for example). Consequently, this quickly leads to pattern distortion.

The fashion industry is actually severely lacking in resources, information and representation that would aid in developing more inclusive size ranges. To my knowledge, no schools (in France at least) exist that specialize in training designers of plus-size clothing, nor how to grade larger sizes. At best, it’s a subject that might be mentioned as a side-note during a course. The best grading manual I know of (Concepts of Pattern grading by Kathy K. Mullet) only goes to a size 50 (UK 22 - US 18).

Undeservedly, plus size clothing has always been considered a niche market. Up until now, sizes going beyond 44/46 (UK 16/18 - US 12/14) have either been ignored by brands, or been presented as part of a mini-collection. On the other hand, certain brands lean exclusively towards this market and offer clothing that begins at size 44/46. According to a study by the IFTH* (Institut Français du Textile et de l’Habillement / French Clothing and Textile Institute), close to 40% of French women are a size 44 (UK 16 - US 12) or above and according to a another American study**, the average size for american women is US 16 - 18. By stopping their collections at a size 44/46 for European brands and around size 16 for US brands, the world of Ready-to-wear is turning away an enormous number of women and in turn telling them that the limit for being valued in our society is a size 44 EU (UK 16 - US 12) or 16 USA.

** Average American women’s clothing size: comparing National Health and Nutritional Examination Surveys (1988–2010) to ASTM International Misses & Women’s Plus Size clothing: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17543266.2016.1214291

![]()

This is all slowly starting to change and terms like plus-size no longer make as much sense. Certain American brands are starting to see that this distinction/stigmatization is not really justifiable when between 40 and 60% of their market is made up of women called “plus size”.

This is all slowly starting to change and terms like plus-size no longer make as much sense. Certain American brands are starting to see that this distinction/stigmatization is not really justifiable when between 40 and 60% of their market is made up of women called “plus size”.

I encourage you all to watch this webinar on the subject. Warning- it has a very “business is business” perspective but is interesting and worth a watch nonetheless.

https://alvanon.com/just-style-webinar-success-in-todays-plus-size-market/

We could discuss the use of different terms used to distinguish size ranges for hours. Calling these size ranges 1 and 2 instead of regular and plus or even alpha or gamma really all adds up to the same thing. It’s not the words that are important, but the meaning that we give the words, and we have to be mindful to not tarnish those words.

As Rivkie Baum, founder of the magazine Slink put it beautifully, " Rather than dropping the plus, shouldn't we be embracing and reclaiming it ? Let’s not make it another dirty word. "

What about inclusivity ?

What about inclusivity ?

![]()

Thinking about concepts and designations, I thus have to admit that the word “inclusivity” makes me feel uncomfortable. It is a fact that I have made known many times in conversation with many of my followers and clients. I decided to stop at size 58 (UK 30 - US 26) because I didn’t feel that, as a small business owner, I was capable of managing on my own more than two size ranges. Developing patterns above a size 58 (UK 30 - US 26) would necessitate (according to me) a third size range and consequently, a third set of new slopers and new grading rule as well as another couture dress form to work and test my patterns properly. I may change my mind in the future, but for now it seems like the best decision for me and my business. By deciding to stop at size 58 (UK 30 - US 26) I have surely excluded anyone with a size 60 (UK 32 - US 28) and above. Because of that, I can’t (and don’t) claim to be a completely inclusive brand.

But what brand can make that claim? In the end, every brand is forced to draft for a certain height, cup size, silhouette etc... This in turn, leads to exclusion of people who don’t correspond with this brand identity.

What is the new norm?

What is the new norm?

![]()

Recently we have witnessed, at least in the sewing community, the effort many brands have made to offer a wider size range. Certain brands have already done the work, others are in the process, some are perhaps thinking about it, while some brands are fearful of approaching this work. Many brands that have already expanded their previous size range (sizes usually maxed out at 46), which means that the new norm has become a size range between 32 to 52 (UK 4 to 24 - US 1 to 20) for European brands and between 32 to 58 (UK 4 to 30 - US 1 to 26) for English-speaking brands. This is definitely a step in the right direction, in my opinion.

I was recently contacted by two sewing pattern brands who hope to expand their own size ranges, one of which is planning on creating two size ranges using what I developed for Readytosew, while another only wishes to add a few sizes to their patterns. I was also approached by a RTW brand that is looking to develop a line of clothing for larger sizes. During all of these interactions, I have been met with the same general observations. The representatives from each of these companies have all started these conversations by saying things along the line of, “We aren’t able to find information or resources. We don’t know what to do or where to start.” In the example of the RTW line, developing patterns in what we would call a standard size range did not pose any problems, the factory that they employ for making their clothing also handles grading and everything was straightforward and simple. It was only when they decided to start their line for women in larger sizes that they realized what an issue this would be for them. The same factories did not know how to move forward. It was like the blind leading the blind. So I did what I could to help these brands, I shared my findings, knowledge and the research that I had done. I am far from feeling like I have completely mastered this subject, nor would I call myself an expert but being contacted by three different companies (one of which is a well-established RTW brand) in the span of only a few months in regards to this issue is certainly telling. It made me realize that what I had been feeling several months prior, that there is a general lack of information and knowing how hard it was to get started- well, I wasn’t alone in these feelings.

![]()

It made me want to share with you all my resources, my size charts, the grading formula I had developed, in short- all that I had learned during the six months I spent developing my new size ranges. I am sure that this could help certain brands open their doors to clients who have been excluded up until this point.

![]()

All of this said, my understanding of the topic as well as the methods I employ are continuously evolving. I am open to all suggestions and advice and to research done by others in this community as well. I would love to be able to collaborate with other companies in order to expand and reinforce what we have learned. Basically, I want this to be a community effort and am open to making that happen.

As for my grading chart, please understand that my methods are not strictly mathematical. I adapt my rules for each pattern I am working with and I also often work very organically. Obviously, this grading chart is tied to my size charts- these two documents go hand-in-hand.

Pattern-Making:

Pattern-Making:

Let’s start from the beginning, shall we? Making a pattern for a fat body is not any more complicated than making one for a thin body. It’s just different. To create my slopers for my second size range, I decided to use a draping method starting with my Alvanon size 50 (UK 22 - US 18) dress form. I started by draping on my plus size form and then I had these slopers (bodice, sleeve, pants) tested on a woman whose body measurements correspond to my dress form. Following these test-fittings, I made modifications to the slopers. I did this for my knits and woven slopers. Once I was happy with them, I began trying to figure out how to grade and how the body evolves between a size 46 and 58. It was the same kind of job I had to do to develop my first size range 5 years ago.

![]()

Grading:

Grading systems are developed to translate the body changes that occur from size to size to the corresponding garment master pieces, after collecting and analyzing anthropometric data from individuals within a target population. A grade guide dictates the system of grade distribution across the pattern. To be able to use a grade guide you need to understand how the body grows. Usually, using the bodice as an example, the width grade is distributed within the neck, the shoulders, and the underarm areas. The length grade is distributed in the neck, the armscye, and the underarm to waist area. The effects of the differences in the sizes where the grade changes and how the grade is distributed within each size are most apparent in the fit of extreme sizes in a size range. Success in grading can be achieved only if a well -developed, accurate master pattern is used.

![]()

How does the body evolve?

![]()

Side note: Obviously, women all have different body shapes and sizes. Recognizing that, we are simply trying to find a way to standardize this data in order to create pattern-making and grading rules that will allow us to create well-fitting patterns. People carry weight on their bodies in many different ways. Some people carry weight up top, around their chest and waist, some carry weight on their hips and thighs, while others’ weight is distributed more evenly.

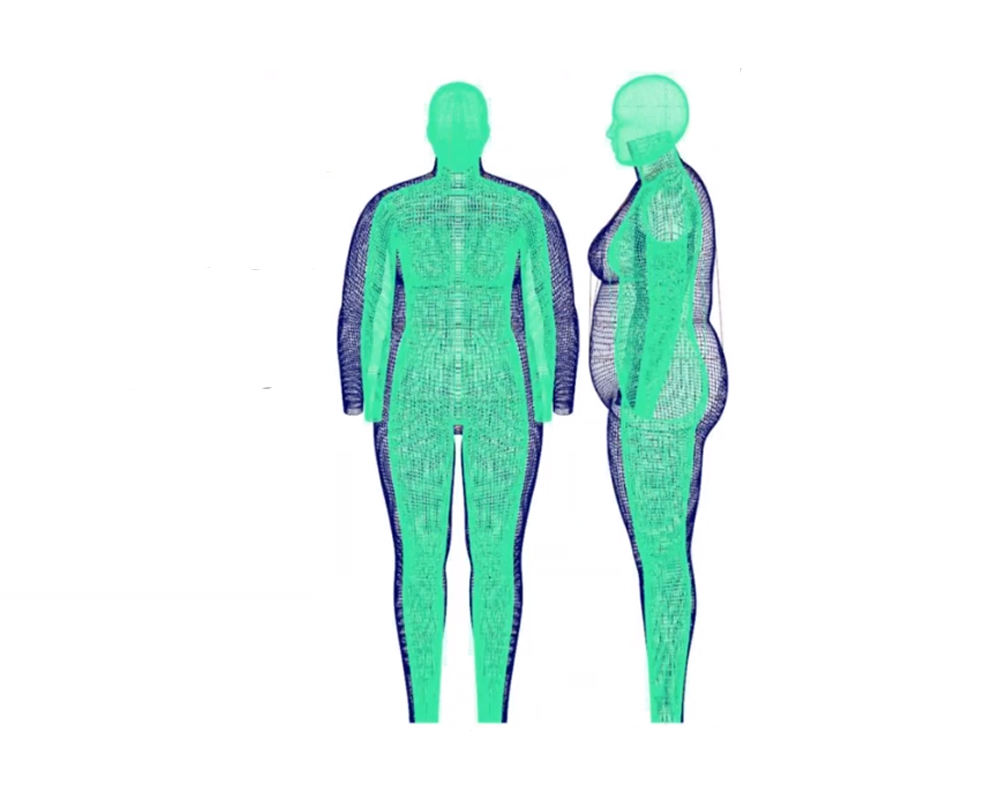

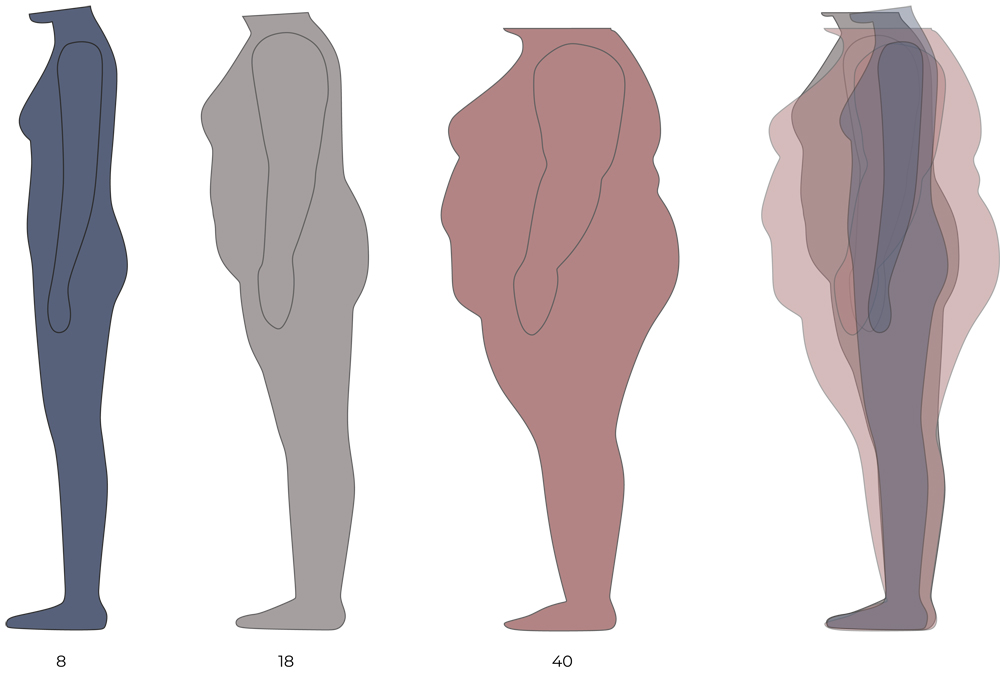

As you can see in the illustration below, the neck base is going to get bigger when going from one size to another, the shoulder will lengthen, the across back measurement will get bigger etc. But to continue endlessly with this formula would require one to believe that from a size 46 (UK 18 - US 14) to a 54 (UK 26 - US 22), the skeleton is much bigger and the arms are much longer- you can see why this doesn’t work! A woman is rarely a size 54 (UK 26 - US 22) because she is built like a professional football player. At a certain point, there is no longer a growth of the skeleton (or maybe only slightly), but not in proportion to the additional body fat. The reason that certain women complain about the length of the shoulder being so important on plus-size clothing is precisely because the base pattern or the grading, or a combination of the two doesn’t correspond with the way the human body actually evolves.

![]()

Image credit: Alvanon

![]()

In the image above, there are two different overlayed bodies. The green body represents a woman who corresponds to about a size 40 (UK 12 - US 8) , while the blue body represents a woman who corresponds to about a size 52 (UK 24 - US 20).

We can see in this image that the length of the shoulder, the neck and ankle circumferences only change slightly when looking at the two different sizes. Except, when a sewing pattern is graded from a size 40 to a 54 with the same grading formula we use for a size range 32 - 46, not only will it be distorted but in addition, the neckline may be too big, the shoulder length too long etc.

The profile image on the right gives us a very interesting perspective on how the body evolves and where body fat is stored. We can see very clearly that the waist is larger and the cup size is not the same. We can also see that the belly is rounder, more prominent and lower on the body, the waist is a little less defined, the crotch will have a tendency to drop lower as soft tissue increases in the crotch area. The body is projected slightly further forward and the back is a bit rounder.

Just by looking at this illustration below, we can see why applying the same grading rules across the board (from a size 32-58 UK 4-30 US 1-26) would be ridiculous and that it’s not a question of simply enlarging a base pattern.

![]()

![]()

![]()

- The plus rise length may become longer to accommodate a larger belly at the front and a fuller seat at the back.

- The inseam is therefore shorter.

- There will be a slight lengthening of the shoulder, due largely to the tissues surrounding the skeleton. The back becomes rounder and the CB-neck to waist will therefore need to be longer. Also, in fitted garment, a shaped center seam will lead to a better fitting.

- The armhole on a plus-size body does not increase with size as much as on a traditional garment grade. If you follow the traditional garment grade method to create an armhole on a plus-size garment, you will probably find it to be too deep on a plus size woman. The biceps, on the other hand, will grow significantly.

- Chest and shoulder darts that can easily be avoided by slim women with small cup-sizes become necessary for a fat woman with a large chest, except in cases of a very loose-fitting or oversized garments.

- I found that pockets cannot just be increased proportionately following the grade guide. Especially patch pockets. They need to get bigger as the patterns get bigger but in my point of view, the size should not be defined only by the grade rules. Keep a critical eye.

- You cannot always translate a straight size garment style on a plus-size. For example, in the case of a straight size pattern with a bust dart rotated into a single pleat in the neckline for a plus size pattern, you would need to accommodate the larger depth of the bust dart by creating two small pleats instead of a large single pleat.

![]()

![]() As for the biceps: after having measured many different women, and analyzed the measurements of my testers as well as collected data via a survey in which 170 people participated, I noted that the size of biceps fluctuates greatly for the same sizes, starting about the 44/46 size range. This makes it relatively difficult when developing a size range to choose one bicep circumference as a standard for the size. Personally, I decided to build in plenty of ease on my plus size patterns, as it is easier for my clients to take in this measurement after sewing than it would be to make it bigger. This is true as well for the calf circumference, which is another wide-ranging measurement.

As for the biceps: after having measured many different women, and analyzed the measurements of my testers as well as collected data via a survey in which 170 people participated, I noted that the size of biceps fluctuates greatly for the same sizes, starting about the 44/46 size range. This makes it relatively difficult when developing a size range to choose one bicep circumference as a standard for the size. Personally, I decided to build in plenty of ease on my plus size patterns, as it is easier for my clients to take in this measurement after sewing than it would be to make it bigger. This is true as well for the calf circumference, which is another wide-ranging measurement.

![]()

![]() As for the cup size: the majority of time, a person corresponding to the measurements of plus-size clothing will not have a B cup. Again, based on the information I was able to find, it is therefore better to use a D/E cup size when drafting patterns. Personally, I developed my pattern blocks based on a generous D cup size.

As for the cup size: the majority of time, a person corresponding to the measurements of plus-size clothing will not have a B cup. Again, based on the information I was able to find, it is therefore better to use a D/E cup size when drafting patterns. Personally, I developed my pattern blocks based on a generous D cup size.

![]() The case of a brand that offers larger sizes without separation of size ranges: Well, personally, as you may have guessed- I am not super into that idea. In my opinion, it is preferable to develop two size ranges as well as two slopers, especially if the size from which the pattern is drafted does not correspond to the middle of the size range. According to studies by both Taylor et Shoben 1986 and Cooklin 1994*, our bodies do not evolve in the same way from the front to back. For example, in terms of the chest size, waist and bicep circumference, women have a tendency to carry more weight on the front of their bodies, which is clearly evident on larger bodies. Despite this, the majority of sewing patterns are graded using the same grading distribution for the front and back pattern pieces. Ex: between a size 34 and 36 there is a difference of 40 mm on the waist size. If grading is done by adding ½ to the front and ½ to the back, we divide that measurement by 4 and we add 10 mm to the front pattern piece and 10 mm to the back pattern piece (which will then be doubled). This method in and of itself is not inherently terrible if the grading is only done for a few sizes, but can begin to cause fit problems if it is applied to grade patterns for multiple sizes. Essentially, the more we can break up the size ranges and create different base patterns, the better (especially for fitted styles). Different studies have recommended that, when using a simplified pattern grading system, it is important to not grade more than two sizes above and two sizes below a base pattern. Studies from Bye & Delong or Murphy ** show that going above these recommendations often results in fit issues.

The case of a brand that offers larger sizes without separation of size ranges: Well, personally, as you may have guessed- I am not super into that idea. In my opinion, it is preferable to develop two size ranges as well as two slopers, especially if the size from which the pattern is drafted does not correspond to the middle of the size range. According to studies by both Taylor et Shoben 1986 and Cooklin 1994*, our bodies do not evolve in the same way from the front to back. For example, in terms of the chest size, waist and bicep circumference, women have a tendency to carry more weight on the front of their bodies, which is clearly evident on larger bodies. Despite this, the majority of sewing patterns are graded using the same grading distribution for the front and back pattern pieces. Ex: between a size 34 and 36 there is a difference of 40 mm on the waist size. If grading is done by adding ½ to the front and ½ to the back, we divide that measurement by 4 and we add 10 mm to the front pattern piece and 10 mm to the back pattern piece (which will then be doubled). This method in and of itself is not inherently terrible if the grading is only done for a few sizes, but can begin to cause fit problems if it is applied to grade patterns for multiple sizes. Essentially, the more we can break up the size ranges and create different base patterns, the better (especially for fitted styles). Different studies have recommended that, when using a simplified pattern grading system, it is important to not grade more than two sizes above and two sizes below a base pattern. Studies from Bye & Delong or Murphy ** show that going above these recommendations often results in fit issues.

While all of this seems self-evident to me, it is difficult to put into practice, very time consuming and expensive for the fashion industry.

*Cooklin, G. (1994). Pattern grading for women’s clothes. London: Blackwell Scientific Publication

Taylor,P.J.,& Shoben, M.M. (1986). Grading for the fashion industry: The theory and practice. London: Hutchinson.

**Bye, E.K., & Delong, M. R.(1994). A visual sensory evaluation of the results of two pattern grading methods. Clothing and Textile Research journal, 12(4), 1.

Murphey, I. C. (1993). A case study of the influence of pattern grading systems on the fit and style sense of two low-neckline, fitted bodices. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA.

![]()

My path, my process

![]()

The trigger

In the spring of 2019, having seen different conversations taking place surrounding the subject of inclusivity on social media, and because I had been contacted by women who were weary seeing that nothing had changed, I started to panic. All of this stressed me out. With a sense of urgency, I decided that my next pattern would be graded to a size 52 (UK 24 - US 20) and I thought to myself, “That’s good enough for now.”

So I designed the Jocko pattern, a loose sweater with dolman sleeves, and I enlisted pattern testers in a wide range of sizes. During the test, I noticed that sizes above my typical 46 (UK 18 - US 14) had small fit issues so I did what I would call little fixes based on the feedback of my testers. I enlarged the armhole slightly, I reduced the size of the neck that was too large, I elongated the bust in order to fit a larger chest etc… It worked. The pattern fit well. But still I didn’t feel sure of myself because, deep-down I knew that I hadn’t really reached the root of the problem. I knew there was still work to be done. It felt like what I had done was cover a wound with a bandaid, instead of investigating the cause of the wound- probably because that task felt so completely overwhelming. And truthfully, I knew that the task would require me to reflect on my own personal beliefs, my way of working, my clients’ needs and my own fatphobia.

It wasn’t until several weeks later that I decided to take my head out of the sand, roll up my sleeves, and finally take the time to develop and create two size ranges instead based on two different pattern draftings and two different grading rules.

![]() Things I have heard with which I do not agree:

Things I have heard with which I do not agree:

- Fat women like the sleeves on their T-shirts to be longer.

- Fat women want longer tops that cover their bodies.

- Fat women prefer wearing black and avoid the color white.

Direct consequence : Why I designed the Primo T-shirt:

When I released my first plus size patterns (The Pekka jacket, the Patsy overalls and the Papao wrap pants), I looked for a t-shirt for my two models Audrey and Laure. I scoured the internet and could find nothing adequate. Those that I was able to find were, as a whole, super big and too long. The necklines were too high on the neck, it was impossible to find a nice round neckline that wasn’t too deep. I decided to order a few of them anyway. When Laure tried them on it was a disaster- gigantic sleeves, busts way too long etc. As a result, I hastily designed a t-shirt for the photoshoot. A few months later, and after many adjustments, the Primo t-shirt, a basic, form-fitting shirt was born.

This example is for me the concrete demonstration that a specific pattern-making is neccesary to enhance the wide range of morphologies.

![]()

The two size range for the Readytosew patterns are thus the result of many observations and much researches, but they are also linked to my desire to make the sewing of well fitting patterns accessible for a wide range of bodies.

I want to reiterate that my knowledge and methods constantly evolve. I am therefore open to advice and team-work and am glad to share my knowledge with other pattern-makers so that the research can be communal.

![]()

Additional Resources:

Below are all of the resources that I consulted in order to develop my two size ranges. If you have any other resources that you think might be helpful, please don’t hesitate to share them in the comments.

- Alvanon Online Course (eng.) https://motif.org/courses/fundamentals-of-plus-sizes/

- Alvanon webinar (eng.) https://alvanon.com/just-style-webinar-success-in-todays-plus-size-market/

- Alvanon couture dress form :

https://alvanon.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/AF-SPECS_ASD_Global_Plus_26JUNE2020.pdf Alvanon creates made-to-order dress forms. These are mostly made for professionals but anyone can order one, However, they can be very pricey. I decided to order a size 50 (US 18), thinking I would stop my second size range at 56. In the end, I decided to stop at size 58 and now I regret not ordering a size 52 (US 20) so that it would have been in the middle of my size range. Ultimately, it all worked out because Audrey, my amazing fit model, is an exact size 50 with a height of 168 cm, just like my dress form, which makes it perfect to try out my patterns on a real body.

-

ASTM's anthropometric data on which I based my own size chart:

https://www.astm.org/Standards/D6960.html I prefered this American reference as opposed to that of the IFTH, which did not correspond with the data that I was able to find. Moreover, Readytosew, being an international brand (60% of my clientele is in Europe, 40% being French and 40% in the United States) it was a little complicated to choose a standard that would best represent an average for my clientele.

- My mentor when learning to grade, Marie-Agnès Peigneguy of “Imagine et vous” with whom I first developed my grading formula according to my measurement charts.

- YouTube Video (eng.): FASHION REAL TALK: The challenges of Plus Size Fashion Design (The Huntswoman)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ac3BfxgA9PY&feature=emb_title

- Article (fr.): Mode in textile by IFTH

https://www.modeintextile.fr/le-probleme-de-taille-des-grandes-tailles/

- Article (fr.) : The body optimist

https://www.ma-grande-taille.com/enquete-mode-francaises-2018

- Book (eng.): Sewing for plus size

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/2040909.Sewing_for_Plus_Sizes

- Blog (eng): Curvy Sewing Collective

https://curvysewingcollective.com/

And finally, one last tip if you will allow me- know that we are sensitized to see patterns made for smaller measurements, with a smaller cup size. When I first began developing my larger size range, I had the tendency to automatically rectify pattern pieces that appeared incorrect. For example, I might shorten the rise depth of a pant leg because it seemed like it was too long. BIG MISTAKE. Or I would add to the shoulder because it looked too short in proportion to the rest of the pattern and to the bust darts. ANOTHER MISTAKE. In short, my advice is this: you are likely going to have to forget a little bit of what you have learned, or what you think you know to be true. You have to be willing to open yourself to different possibilities and to share with others what you have learned.

![]()

Help yourself

In the spirit of my final tip- you will find below my grade guide as well as my grading distribution system and methods- free to download and share. Tag me @ready_to_sew or use #readytosew on Instagram.

![]()

- You can download here my grade guide for size range 46 to 58

- You can download here my grade distribution for the size range 46 to 58

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the following people, without whom you would not have been able to read this article:

Thank you to Michèle and Perrine for offering help in reviewing and revising the article for grammar and syntax.

Thank you to Laine for offering help in reviewing and revising the article for grammar and syntax and for the english translation.

Also on a side note: thank you for listing all the resources and splitting them up topic-wise (instead of cramming them all together at the end)!

Et merci pour cet article si intéressant !

Il y a quelque temps déjà que je me suis résolue à abandonner les marques qui s'arrêtent au 46. Je me suis fabriqué un patron de base que je décline en fonction de mes besoins. Mais c'est tout de même frustrant de devoir renoncer à certains modèles que je rêverais de porter. Je précise que je navigue et grade entre le 48, 50, 52 selon les modèles et la morphologie auxquels ils s'adressent .

Merci et meilleurs vœux.

Je n'ai aucun projet dans le patronnage de vêtement, excepté pour moi, mais cela précise des points dont j'avais pris conscience grâce à Jenny Rushmore, et grâce à l'évolution de mon corps.

Je me trouve juste à la limite entre les tailles standard et les grandes tailles, globalement entre 44 et 46, et j'ai eu une épiphanie le jour où j'ai pu essayer des pantalons en 46 dans un magasin qui a une gamme grande taille : oui ça me va mieux. Parce que la coupe n'est pas la même m'étais-je dit ! Et je comprends maintenant que c'est une question de référence de base... Bref, un grand merci, je pense que c'est ce genre d'article qui peut effectivement faire avancer les choses concrètement !